Judge Arthur Gajarsa: ‘The federal government has a trust responsibility to protect tribal interests’

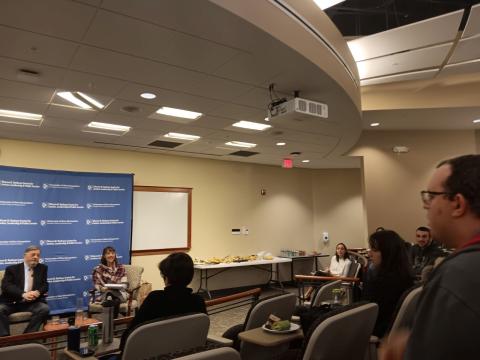

To better understand the current state of Native American affairs, we must relearn history, said Judge Arthur Gajarsa during a recent discussion on Federal Indian law and tribal sovereignty. The event was hosted by the Warren B. Rudman Center for Justice, Leadership & Public Service in recognition of Native American Heritage Month. Rudman Center Community Engagement Director Laura Knoy moderated the discussion.

“History was essentially written not by the victims, but by the victors,” said Gajarsa, Jurist-In- Residence at the UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law, where he also teaches Federal Indian Law. Gajarsa has extensive experience representing tribal interests and also served as special counsel and assistant to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs at the Department of the Interior.

Judge Arthur Gajarsa discusses Federal Indian Law during an event hosted by the Rudman Center.

For the full video, visit here. Quotes in this piece have been edited slightly for clarity.

The Iroquois Confederacy, for instance, with its separation of powers and policies that included referenda, vetoes, and protection of certain personal freedoms, significantly influenced the framers of the U.S. Constitution, Gajarsa said. One particular aspect of the Confederacy, however, would take generations to come to fruition: Women had a large role in tribal government.

“If you go back and start from the time of 1492 forward, you have to start adapting the history books to make people understand the actions in the days when immigrants from Europe and other areas, coming in as colonials, believed they had a manifest right to go from ocean to ocean. That was a big theory of the federal government at one time -- that we were going to have a United States going from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

And to those colonials, Native American tribes were standing in the way of Manifest Destiny, a concept that would lead to the forcible removal of Native Americans from their land and legal battles over tribal sovereignty that continue to this day. It was not until 1924, a mere 100 years ago, that Native Americans were granted citizenship without conditions.

Judge Gajarsa has been involved in some of those legal battles, arguing several times before the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of tribal nations, including a case involving water rights in southern California that took decades to be resolved – finally in the tribes’ favor.

In the past 25 years, the Supreme Court has ruled frequently against tribal interests, he said, with a few notable victories. The Haaland v. Brackeen decision in 2023, for instance, preserved the system that gives preference to Native American families in foster care and adoption proceedings involving Native children. (Visit here for the Rudman Center interview with Prof. N. Bruce Duthu on this decision.)

Laura Knoy of the Rudman Center and Judge Arthur Gajarsa of UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law.

Judge Gajarsa also discussed the role played by several American presidents in either upholding or upending tribal rights. Andrew Jackson, for instance, ignored the Marshall Trilogy, a trio of decisions in the Marshall Court that formed the basic framework of Federal Indian Law. Jackson encouraged Congress to adopt the Removal Act of 1830, which would eventually lead to the “Trail of Tears,” the forced migration of the Cherokee tribe from their ancestral lands to new territory west of the Mississippi River. Between three and four thousand Cherokees are believed to have died during that brutal journey.

President Richard Nixon, Gajarsa said, bolstered tribal sovereignty. Nixon oversaw the return of sacred lands to tribes and pushed to end the government’s so-called “termination” policy, which had worked to dismantle tribal governments and eliminate reservations. Instead, Nixon promoted self-determination, empowering Native Americans to govern themselves.

There have been legal twists and turns since then, including a 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision that gave states unprecedented power to prosecute certain crimes in Indian country. The U.S. Dept. of the Interior described the decision this way: “The decision drastically altered the status quo, overturning nearly 200 years of law enforcement practice nationwide where federal jurisdiction over crimes committed by non-Indians against Indians in Indian country has always been exclusive of state jurisdiction.”

But Gajarsa said some recent developments have given him hope.

“The process right now is self-government, which I think is helping to tip the balance of justice in their favor, which is the beginning of an equilibrium,” he said. “It's never going to be equal. It's never going to be totally corrected, but at least we're in the process of trying. And that's important. The federal government has a trust responsibility to protect their interests.”